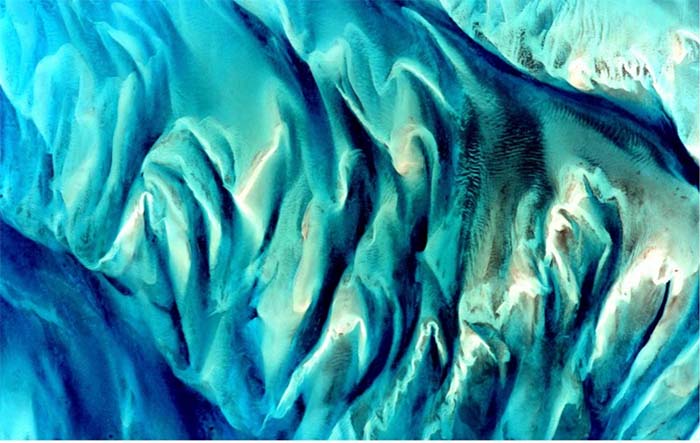

Bahamas, “the most beautiful place from space”

#yearinspace, Scott Kelly, Astronaut

We left West Palm Beach, FL, at dawn and made a 7-hour passage to West End, Grand Bahama. As we approached West End Harbor, schools of flying fish appeared off our starboard bow. We followed a Canadian sailboat through the narrow coral-lined channel walls and were greeted by the smiling faces of two able Bahamian dock hands who secured Kailoa in her slip by 3 p.m. We both breathed a sigh of relief because the passage went as planned. (see previous post)

Bahamian people are known for being warm, friendly, hospitable, and extremely polite, and we absolutely found that to be true. We were invited to have conch salad and a rum punch while clearing customs and to the Junkanoo celebration at the West End settlement. Junkanoo is a celebration and street parade where locals dress in elaborate costumes to ring in the New Year with a steady beat of drums, whistles, cowbells, and horns. “We will provide transport to the celebration; just check in at the desk,” said one of the marina attendants. When we inquired about tickets and the cost of transportation, a woman replied,” Show up at 3 a.m.; it’s $5.00 a person round trip, including a bleacher seat.”

Kim was struggling with a cold, and we were both weary from the travel and anticipation of the Gulfstream crossing, so we sadly missed the 3 a.m. parade. On New Year’s Day, we lounged on the beach and watched sea turtles bob their heads above the water’s surface to gulp air before returning to munch on the field of seagrass below, which extended for miles on the eastern shore.

The warmth of the Bahamian big smiles and welcoming greetings, along with their intention of making a point of direct eye contact, was palpable. We removed our sunglasses to ensure the people we talked with could see our eyes.

We quickly learned that conch is a national staple on every menu and is served in abundance. It’s a mollusk or sea snail that lives in a beautiful shell. The meat, firm and white, is the national dish of the Bahamas. Conch can be prepared in several ways: fried, frittered, stewed, or prepared as a salad, raw with lime juice and vegetables.

Although it was a high holiday, we found West End to be a sleepy, quiet place that provided a respite for fishermen and cruisers alike. The resort had a few townhouse-style buildings for guests, a fuel dock, a restaurant, and a pool. The locals who worked in the marina lived in the settlement three miles down the road. While the Bahamian spirit is West African, many of its laws and traditions are British, such as driving on the left side of the road, the Westminster parliamentary system, and even drinking tea as a daily routine.

The day after New Year’s, we rented a golf cart to explore the central West End settlement, population 100. Livable and unlivable buildings lined the two-lane road to the settlement. Many homes were abandoned and in disarray, missing roofs and windows encased in dense vegetation. Enormous piles of Conch as high as 10 feet in spots lined the eastern shoreline.

We stopped at Sherry’s on Da Westside for lunch. Our bowl of pickled Conch with onions, hot sauce, and lime was unique. The young man (Grahm) who prepared the dish sat beside us as we ate. We asked Graham why his leg was in a brace. Without hesitation, he explained that he had a significant accident at the Freeport Shipyard. His supervisor asked him to clean a tank. He asked about safety equipment, including a respirator, harness, and headlamp. His supervisor told him to “just go in and clean it.” Grahm’s story revealed that he fell 65 feet into a dark fuel tank with about 12 feet of standing diesel. On the way down, he cut open his head and splintered his knee. Somehow, he managed to survive the fall and remain conscious. He described putting his paper mask on to avoid passing out from the fumes and waiting in the dark tank injured for 45 minutes before help arrived.

With significant head trauma, he was transported to the hospital in Freeport. When his father saw that he was “going down”, Grahm’s daddy advocated to hospital staff to have him airlifted to Nassau for better care. A big scar ran from Grahm’s right temple to the back of his head, along with another scar that ran the three-quarter length of his left leg. Graham commented that he has been out of surgery for almost a year and is doing well. There was no bitterness in this young man’s heart. He was a happy soul, and we laughed about how he is the luckiest man alive.

We asked Graham about the abandoned buildings; he told us they were destroyed during Hurricane Dorrian in 2019. During the storm, the water level rose 8 feet above the land surface where we sat. Graham described how the massive piles of Conch were pushed into the street. “The hurricanes are more intense,” he added. We also asked Graham about the piles of Conch. He said there were over 2 million placed along the shore as fill. We asked Graham how the tourist season was; as he chuckled, he replied, “There’s no tourism here; that’s in Nassau.”

We also met Harold, a 70-year-old man with a dark face, kind white eyes, bristled white whiskers, and tightly cropped white hair. Our locked-eyed conversation about the state of the US lasted a few minutes, but it could have lasted for days. He let us know about the horrific killing in New Orleans and was deeply distressed. He commented that he doesn’t understand how humans could possess a blatant disregard for human life; “we are all in this together.”

We collected a few conch shells and sea glass on a local beach, talked with other travelers, and enjoyed more conch salad prepared by Harry on the pier. For a fee of $10.00, a local baker delivered warm Banana Bread to our boat. We celebrated New Year’s a day late with some cruisers that we met from Kentucky.

A vintage feel at West End brings back a childhood feeling of a kinder, gentler, community-centered place in time.

The next stop is Port Lucaya, Grand Bahama, on the south side.

Kailoa signing off!

Leave a Reply